Usually you’d have to wait for May 15 for Nakba observance – that’s the date on the secular calendar that those sympathetic to the Palestinian narrative mourn the founding of the State of Israel as their “nakba” (catastrophe). The Nakba historically coincides with Israel’s establishment. Though David Ben-Gurion had formally declared the Jewish yishuv’s independence on Friday afternoon, May 14th, 1948 (the 5th of Iyyar, the date on the Jewish calendar which is celebrated annually as Yom Haatzmaut, or Israel Independence Day), the State of Israel technically would be realized only from the moment that Britain was set to relinquish their mandate (Friday night, 12AM, May 15). At 12:01 AM, Abdullah of Jordan stepped westward onto the Allenby Bridge and fired his gun in the direction of Jerusalem, joining four other Arab countries in war against the minute-old State of Israel. Their collective defeat spelled massive displacement for local Arabs into other lands and nearby cities, the dismantling of villages, and the formation of a strong and vibrant Jewish state, all reasons from the Arab perspective for a day to mark what they view as a disastrous outcome.

This year, Nakba is coming early…and right to my backyard.

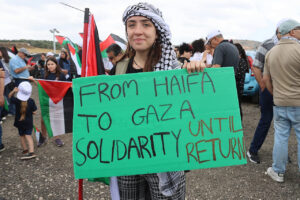

That is because the Committee for the Defense of the Rights of the Internally Displaced Persons in Israel organizes their annual “March of Return” on Yom Haatzmaut, which usually falls a few weeks prior to March 15. The organization selects one of the depopulated and destroyed Arab villages as their destination, marching under the slogan “Their Independence is Our Nakba.” As they have done in growing numbers (one write-up touts 15 thousand marchers, while another, chronicling a different year, claims 30k participants) over the past twenty-seven years, they will wave Palestinian flags and call for the right of Palestinian return to all of the places in Israel that were abandoned or destroyed in 1948.

This year, they are planning to gather on a broad, empty plain around half a kilometer from my home in Sde Ilan in the Lower Galilee. They intend to march from Kfar Kama, the neighboring Circassian village with whom we historically have had warm and friendly relations, to the site of what was once Kfar Sabt.

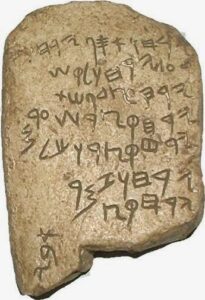

A word on Kfar Sabt: in the Talmudic period, the verdant plain on the southern bank of the Adami riverbed, which bisects Sde Ilan, was home to a Jewish village called Kfar Shabtai. A thousand years later, in the Mamluk period, a few Arab families settled on the ruins of Kfar Shabtai, and preserved the original name of the town. The tiny holding barely held on until the 1830s, when a wave of Algerian Arabs migrated to the Lower Galilee region and settled in four main villages, including Kfar Sabt.

In 1948, Kfar Sabt, along with some of its hostile neighbors like Lubia and Sejera, whose residents had joined the Fawzi al-Qawuqji’s Army for the Liberation of Palestine in raiding and attacking the surrounding Jewish settlements during the War of Independence, was depopulated. The inhabitants fled to nearby Arab towns that hadn’t attacked Israel, such as Kfar Kana and Nazareth. Now, thousands intend to march on the agricultural tracts abutting our moshav, brandish Palestinian flags and, in the words of the organizers, rile the crowds with “fiery speeches…on the grand hopes and vision of return” to Kafr Sabt.

The Lower Galilee Municipality sent a strongly-worded letter to various authorities, including the police, based on principled and practical objections to the planned march. They cautioned against holding a Nakba event within the jurisdiction of a municipal authority in the State of Israel on Yom Haatzmaut on the grounds that it was provocative and inflammatory. Especially at a time of heightened national security concerns in our ongoing war, the letter said, such a gathering posed a tangible threat to public safety and property.

Make no mistake: the municipality is not overreacting. This gathering is no peaceful call for coexistence, nor is it a benign heritage tour to educate Arab youth about their ancestors. It is an incendiary call for Arabs who self-define as “Palestinians living in Israel,” many of them my neighbors here in the Lower Galilee, to exercise their “right of return” to villages that no longer exist. It is a virtual cri-de-coeur against the State of Israel, a deliberate targeting of the celebration of its establishment.

The organizers minced no words in describing their agenda. In describing her anticipation for the march to Hittin (like Kfar Sabt, once a Jewish village in the Talmudic era), journalist Samah Saleibeh wrote in 2021: “we were full of motivation to leave our homes and take part in something massive—something with national and emotional significance—on Israel’s national holiday…Arab citizens longed for a unifying event with broad consensus.” She reflected on her experience: “The large marches, initiated by young and energetic activists from the third generation of the Nakba, instilled in me—and in many others—tremendous hope: that our collective memory as a people is still alive and kicking, still waiting for us.” She further chided the older generation that it was time for the younger, more defiant torchbearers to lead the cause: “The fear of the police, and of what the Jewish neighbors might think—those who may disapprove of images showing thousands of Palestinians marching with Palestinian flags—needs to be left behind.”

Commenting on last year’s march, which also took place in the Lower Galilee and in the shadow of daily rocket barrages from Hezbollah, Makbula Nassar, one of the event’s organizers, stated the following: “We are not compromising on continuing our activity, which has been going on for years. Its value has grown in recent years as a unifying event that speaks to all members of Arab society.”

In front of a backdrop featuring the entirety of the State of Israel as the symbol of the nationalistic aspirations of this event, rapper Tamer Nafar performed last year. “The crowd was a mix of young and old, men and women, babies and teenagers,” Nafar continued. Going beyond Saleibeh’s hope for the young adults of the “third generation,” Nafar is confident that the aspiration to return to pre-48 borders has taken strong root even among the youngest members of the “Palestinians who live in Israel” (Israeli-Arab) community. “This in itself is a source of light that will fill me with hope for some time. It’s very moving to see Palestinian kids at the march singing Palestinian national songs. A long time ago, Israeli leaders thought the third generation of the Nakba will forget. This is the fourth generation and they still remember.”

A number of years ago, I visited an elementary school in Sakhnin, an Arab city in the Galilee. I had asked the principal how they celebrate Yom Haatzmaut, and he responded that since the school’s culture includes honoring those who identify as “Palestinians living in Israel,” they do not observe the holiday. I thought of that as I read Nafar’s reflections. He is right to be hopeful regarding these youngest Israeli Arabs, or alternatively, as they are increasingly self-identifying, “Palestinian kids living in Israel”–they are being educated to nurture the hope that they will one day repopulate and rebuild Kfar Sabt.

How much press has this annual march for the “right of return” for Arabs within Israel received in national or international news over the last three decades? I will admit, as an Israeli Jewish citizen of the Lower Galilee, I only learned about this when it came knocking on my doorstep. It was a somber wake-up call for me, and for us all, to pay very close attention to what our Arab neighbors within Israel–in growing numbers, and with growing boldness–aspire to. This year, if the march is held as planned, thousands of Palestinian flags will parade across my backyard as I stand holding my degel Yisraeli. I write this as a warning that next year, it could be your backyard.